In the past I have needed to measure the amount of bird calling activity to see how the vocalising behaviour of birds in general responds to changes in sunlight. So, how should the amount of bird calling activity be quantified? One way might be to use any number of acoustic indices that have been developed to estimate biodiversity. These indices that calculate acoustic properties generally are to do with the amount of acoustic activity and the variety of different kinds of events, so, using acoustic indices would be an option. However, the relationship between the index values and the behavioural response is not clear. Ideally, we’d also like a less opaque, more direct measurement of bird calling activity.

To get this direct measurement we tried counting the number of bird vocalisations. Naively, this seems reasonable if not tedious, but, of course, it is not always obvious what constitutes a single vocalisation. Bird vocalisations are built from simpler elements hierarchically. Some are much more complex than others. Do we count single syllables, phases, songs?

What about repetitive vocalisations? Because of the huge variety in the way birds produce repetitive vocalisations, it is often unclear what should be included within a single annotation. Some calls are periodically repeated with clear pauses in between, and in those cases it might make sense to count each of those repeated vocalisations separately. Others are repeated so fast that they should be counted as one continuous vocalisation that oscillates in amplitude. At what threshold are the repetitions close enough together to count it as one single vocalisation? Does it matter how complex each repetition is?

Another question is should the duration of vocalisations also be considered? It seems reasonable to regard a repetitive call that lasts 10 seconds as contributing more “bird calling activity” than one that lasts one-second. So, maybe some combination of the number of vocalisations and the duration would be better.

Clearly there is no one perfectly correct way to quantify bird vocalising activity that works for all species, but that is probably okay. What is very evident is that the way we choose to address these questions will affect the final measurement, and it’s therefore vitally important to count vocalisations in a consistent way. Without an explicit protocol, it is easy to be inconsistent, which can introduce bias into results that rely on annotation counts.

Annotating syllables

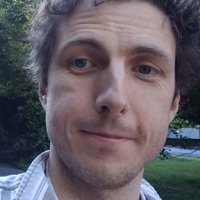

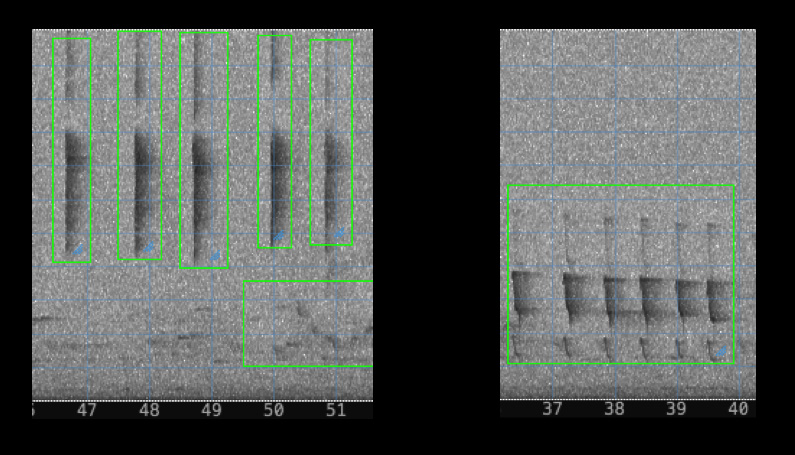

Let’s look at some example spectrograms. In these two 15 second clips, all the bird vocalisations have been manually annotated by drawing a box around them for the purpose of quantifying the amount of bird vocalising activity. The boxes represent the start time, end time and top and bottom frequencies.

Two annotated audio clips with different amounts of bird vocalisations

Some vocalisations are very simple, some are more complicated, and some have many repetitions, but it is pretty clear that the top one has more vocal activity than the bottom one, and this is reflected in both the number of annotations and the total combined duration of annotations.

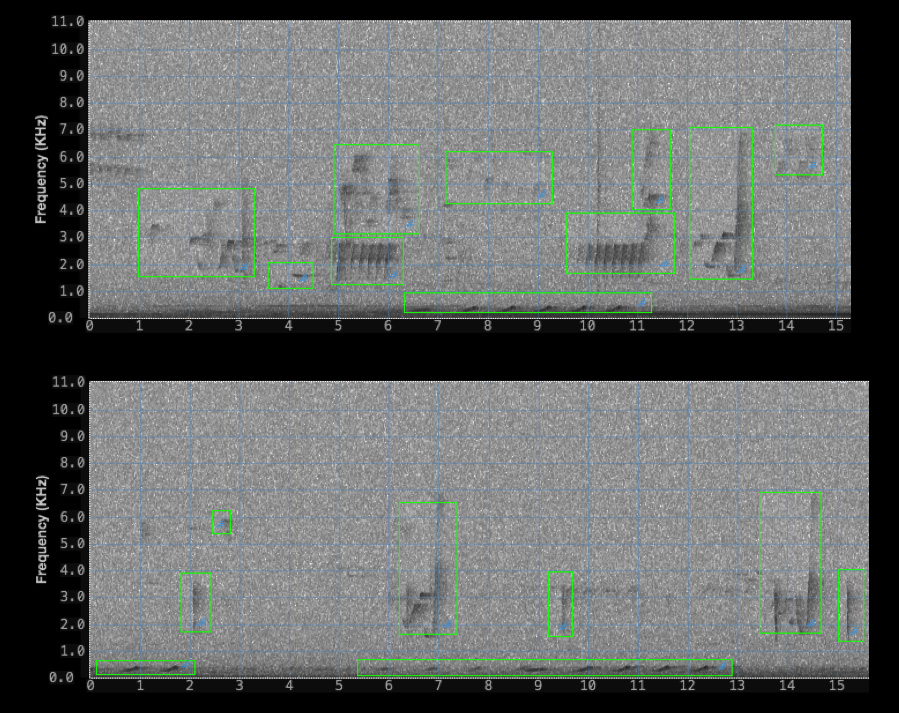

So far so good, but before doing this annotating for very long, we start to run situations where it’s not clear how we should annotate, and the choice we make would have an effect on the end results. Below are 4 short clips of spectrograms.

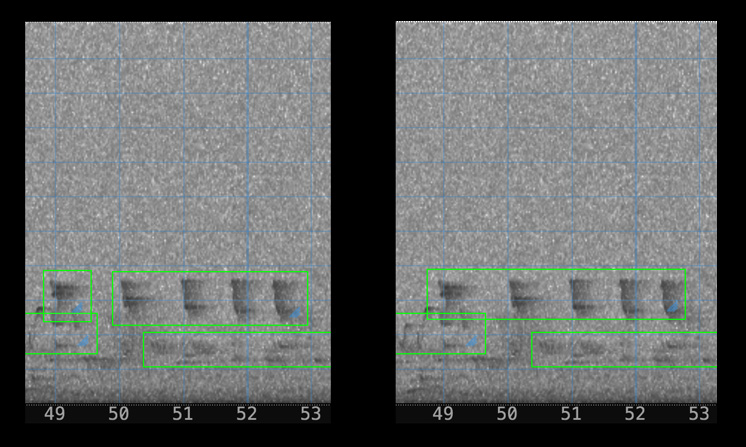

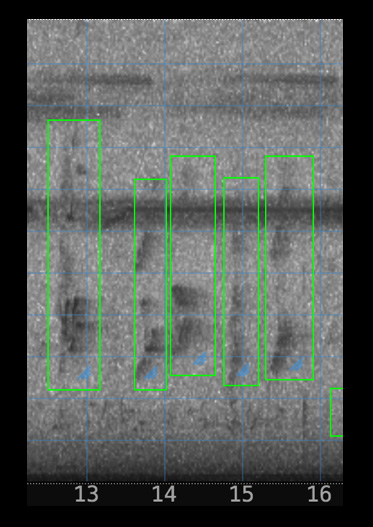

Four repetitive vocalisations with different repetition rates

The top left one it seems natural to put a single annotation boundary around the sequence of repetitions, since they are just about overlapping. But, what about the other three? Should they each have the repetitions all grouped together, or should each repetition be annotated individually? If we group them together, then we will have a lower count for number of vocalisations but a higher count for duration, since we are also counting the inter-syllable space as part of that duration.

These examples illustrate the need for a set of rules about how these annotations are drawn so that the measurements would stay consistent. It is problematic to just do what feels correct, because that can change during the time spent doing the annotating. The following examples illustrate the protocol I developed for this experiment. This exact protocol I used is not necessarily applicable to other recordings and situations; however, understanding the unexpected complexities of defining its set of rules can inform the design of different annotation protocols for other studies.

This is what I came up with:

- Single syllable repetitive call: group repetitions if they are less than 1 second apart

- Multisyllable repetitive call: group repetitions if they are less than 0.75 seconds apart

- Continuous chatter: group everything

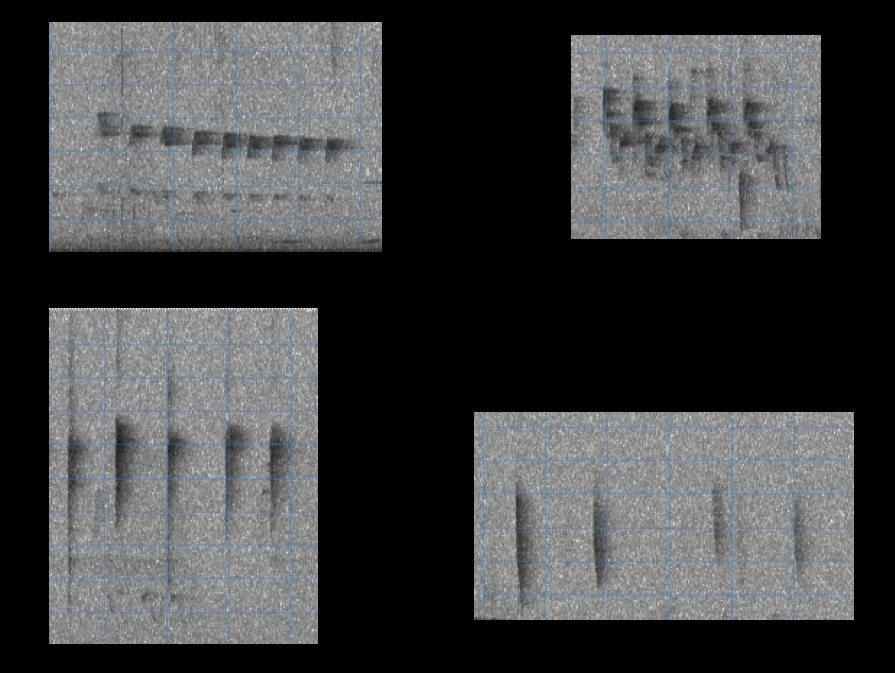

Here are two examples of single syllable repetitive vocalisations. The one on the left has repetitions that are more than one second apart (from start to start) and are therefore separated. The one on the right has repetitions that are less than one second apart and so are grouped together.

Two repetitive single syllable vocalisations with different repetition rate, annotated differently

Repetitive calls with many syllables in each repetition have a slightly different threshold than for single syllable repetitive calls. Applying the single syllable rules to multisyllable repetitive calls seemed to result in groupings that didn’t intuitively feel right. Below are two are examples of multisyllable repetitive calls. The one on the left is separated because the repetitions are more than 0.75 seconds from start to start, and the one on the right is grouped because they are less than the 0.75 second threshold.

Two repetitive multi-syllable vocalisations with different repetition rate, annotated differently

How were these thresholds determined and why should it be different for multisyllable or single syllable calls? The answer is that it is somewhat arbitrary but ultimately just what seemed best, without having any specific knowledge about the meaning attached to the different call types. The fact that I was naturally more inclined to split multi syllable repetitions into separate annotations just shows that if I had just relied on what seemed right on a case by case basis, with all of the endless variations, I would have certainly annotated the audio inconsistently.

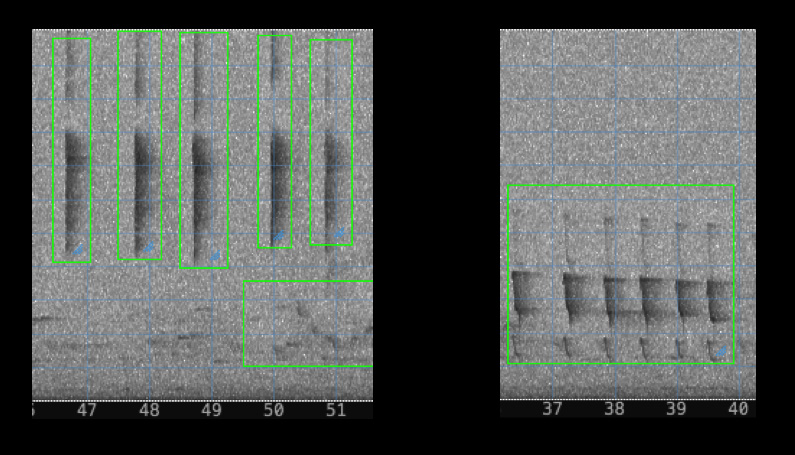

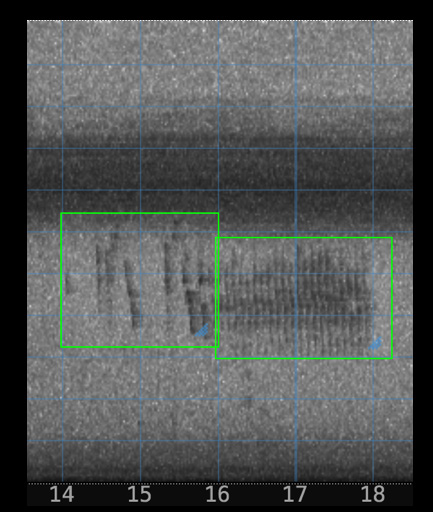

As we keep annotating, we find new patterns where the rules we have so far defined are ambiguous. Take a look at the following example.

Two interpretations of the threshold rule applied to the same sequence of repetitions

This shows the same sequence of repetitions annotated in two different ways. The space between the first and second repetition is longer than the threshold, so maybe it should be split into two separate annotations, like in the left example. However, the average distance between repetitions is less than the threshold, so we could be justified in annotating it all as one, like on the right. I chose to use the average distance and annotated like on the right-hand example. After all the threshold is arbitrary; if the second and third repetitions had occurred slightly earlier, there would be the same amount of vocal activity, but none of the gaps distances between repetitions would be greater than one second. So, the rule was amended to specify that it should be the average distance that the threshold applies to.

How long can one annotation last?

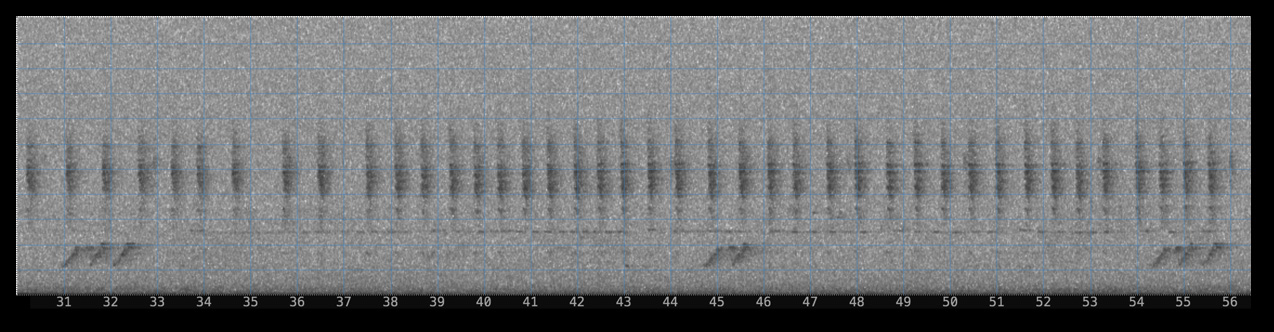

The example below shows part of a repetitive vocalisation that lasts for more than 100 seconds

Repetitive vocalisation that lasts for 100 seconds (truncated to 30 seconds)

According to the rules above, they should all be grouped into a single annotation. But surely, if we are relying on the number of annotations to calculated bird calling activity, this single annotation would be an underestimate. This might not matter if we are going to also incorporate the duration of the annotations into the calculation, but, for the purpose of keeping things manageable, and so that the annotation count can be used without the duration, A rule was added that the maximum duration of an annotation of a repetitive vocalisation is five seconds. I am not sure if this was the best but it worked well for my research. Given a different objective, maybe it should have been 10 seconds or had no upper limit at all. But, at least this way, I have a rule that is easy to follow, enforcing consistency.

More ambiguity

There were a few more details to the rules that I added upon encountering cases were the ambiguous. Here are a couple of examples

Vocalisation that abruptly changes repetition rate

Two individuals producing the same repetitive call type simultaneously

On the left is a case where the same individual changes the pattern during a repetitive call. In this case, two annotations were used: one for each part of the vocalisation.

On the right is a case where the two individuals of the same species simultaneously produce repetitive vocalisations. The rules are applied to each individual separately (which is easier to notice by listening), meaning, in this case, that the distance between repetitions is greater than the threshold and they are therefore annotated separately.

Conclusion

I haven’t put an exhaustive list of all my rules here, because the more specific the rules get, the less likely it is that they will be applicable in other situations. What I hope to illustrate by sharing this is that first, there is a lot more to think about when fully annotating bird vocalisations than there might appear at the outset, and second, that in order to keep things consistent the annotators must create and follow a set of rules. This would be even more necessary if the task of annotating were shared by more than one person!