A marine microphone is shown in the above image. It is made of a hard ceramic material. Most hydrophones are based on a special property (piezoelecticity) of certain ceramics that produce a small electrical current when subjected to pressure changes. When submerged in water, a ceramic hydrophone produces small-voltage signals over a wide range of frequencies as it is exposed to underwater sounds propagating from any direction. See this article for a discussion of how sound is produced and transmitted through the ocean. A hydrophone can “listen” to sound in air but will be less sensitive due to impedance mismatch. It is designed to have a good acoustic impedance match to water, which is a denser fluid than air.

Of course, like terrestrial microphones, hydrophones must be attached to considerable electronics to process and store the signal. Hydrophones are usually classified according to whether they are cabled or uncabled, anchored or free-floating. Cabled hydrophones are usually supplied with power through a cable connected to the shore. Uncabled hydrophones depend on batteries. For example, the hydrophones used by the Cornell Lab (see images below) depend on 40 defence-grade D-cells. These along with the electronics are stored in a water-proof “float”.

A marine hydrophone showing one of two cradles containing 20 D-cells.

The ceramic hydrophone is stored in a white cradle to front side of the float. The float has been cut away to show the internal electronics and some of the battery storage.

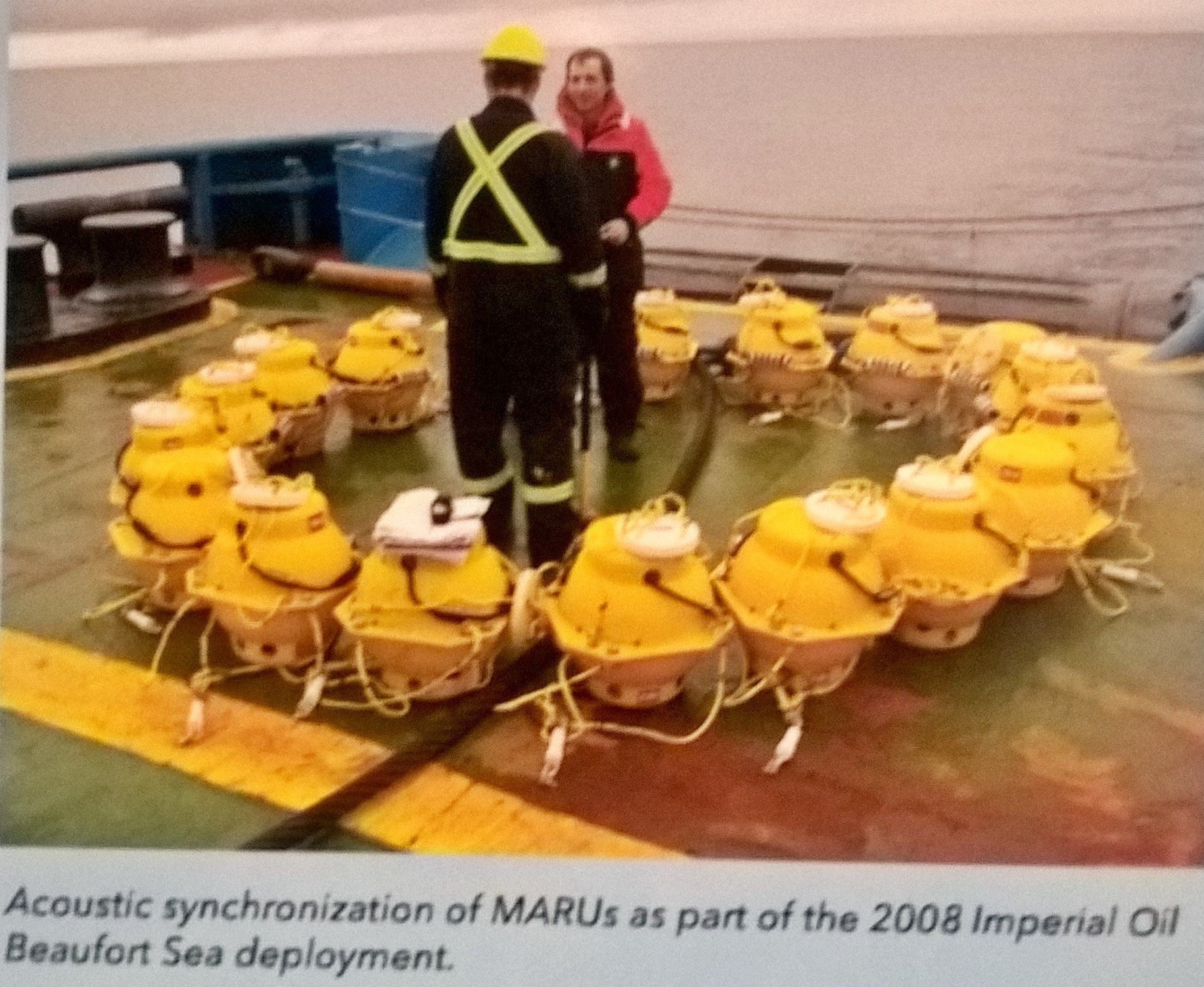

Eighteen hydrophones in process of being synchronised prior to deployment at sea.

Ernest Rutherford, the famous new Zealand scientist who first split the atom, led pioneer research in piezoelectric hydrophones. They were already in use in World War I, by British convoys as protection against U-boat attack. Although hydrophone research has been driven by the concerns of naval warfare, today they are indispensable in marine research.